"People will ask: 'But you love your kids, right?' Of course, I love my kids— that's not the issue. We don't have to always say that when we are talking about how hard it is to be a mother." Karin Tanabe joins Zibby to talk about her sixth novel, A Woman of Intelligence, and how it portrays motherhood in the 1950s. The two discuss some of the shocking historical events that were featured in the story, the influence Karin had on the cover art, and how writing, like all art, requires time and practice.

Noa Tishby, ISRAEL

Actress, activist, and author Noa Tishby recently joined Zibby for an in-person event to discuss her new book, Israel: A Simple Guide to the Most Misunderstood Country on Earth. Tishby talks about her activism, the source of most anti-Semitic attacks on the Internet and across America, and why it's so important for everyone to educate themselves on the history of the hotly contested region.

Laila Tarraf, STRONG LIKE WATER

Zibby is joined by Chief People Officer for Allbirds Laila Tarraf to discuss how three significant losses made her reconcile the tenderness of her personal life with the strength she had acquired in the business world. Laila shares the most valuable lessons she's learned from her bosses through the years, and how combining courage and compassion may be the most advantageous thing you can do for both your personal and professional personas.

Abigail Tucker, MOM GENES

Abigail Tucker joins Zibby to break down the science in her latest book. The two talk about the research that is being conducted on how "mommy brain" is a real biological phenomenon, how the way we treat new mothers can have a psychological impact, and how our own mother's genes may still be inside us today.

Adriana Trigiani, REUNION BEACH

"We always just pretended like we knew each other for a hundred years because that's what it felt like.” In her moving interview with Zibby, Adriana Trigiani lovingly recalls her late friend and fellow writer, Dorthea Benton Frank. Between anecdotes, Adriana discusses her experience of growing up in Appalachia, her decades of reinvention, and the art of drama.

Sherry Turkle, THE EMPATHY DIARIES

MIT Professor Sherry Turkle has long been revered for her research on society's relationship with technology. In her newest book, The Empathy Diaries, she blends her research with her own narrative as she analyzes the various roles empathy has played in her family history. Sherry talks with Zibby about how her relationship with her mom continues to evolve and the ways in which writing this book began to heal some of her old wounds.

Julia Turshen, SIMPLY JULIA

“It’s like you unveiled yourself over every dish.” Zibby talks with cookbook author Julia Turshen about the deeply personal nature of Julia's 15th cookbook, including its revelatory essay on body image and self-worth. They discuss cooking when you don’t feel like it and the pandemic’s impact on the cookbook.

Anna Malaika Tubbs, THE THREE MOTHERS

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Anna. Thank you so much for coming on "Moms Don't Have Time to Read Books."

Anna Malaika Tubbs: Thank you for having me. It's really an honor.

Zibby: It's an honor to talk to you. You're such a genius. This book was amazing. Your book is called The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation. Can you please tell listeners what this is about? Even though this cover is amazing and the title is amazing, I still think it's about far more than just those women. This is essentially -- you know what? I'll let you do it. [laughter]

Anna: No, you were doing great. I was like, keep going. It's about the mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin. Alberta King, Louise Little, and Berdis Baldwin were their names. It's also about what they symbolize in terms of black American womanhood throughout an entire century of American history and what they lived to witness, but also what they lived to inspire through not only raising their children, but also through their teachings outside of their families and their communities and in the many ways that they still inspire us today even though so many people don't know their names. It's all about telling their story, taking them from the margins, putting them in the center away from the shadows into the spotlight like they deserved to be all along.

Zibby: That's amazing. You also go back and give us so much rich history of so many places, people, generations. Some of the things, even from something like Deal Island and how that started or the immigration from one country to another, you painted such a picture of history in general. When I was reading it, I was thinking, this is like the textbook -- that sounds negative because textbooks are terrible. Now I feel bad. If you're a textbook writer, I don't mean your book is terrible. How about this? This should be required --

Anna: -- They're not usually as readable. It's a little harder to get through them.

Zibby: Yes. Required reading on the history of black America in general, especially from the lens of women. Still, you have so much information in here. Yet you wove it together in a narrative form to make it highly digestible. I thought that was awesome.

Anna: Thank you. That was a big goal of mine. It was an important one. I wanted it to be a text that people could refer to in terms of learning about American history through this perspective of three black mothers and how that changes the way we view events like the Great Depression, thinking about the Great Migration and actually getting to know participants in it, all of these things that we think about, both of the world wars. There's so many different things that they lived to see, multiple different presidents and the way their policies affected them differently in each of the three cases because of their own access to resources and education. I think it allows you to better understand history. I appreciate you taking note of that.

Zibby: It's great. People are always like, we should rewrite history. You did it. There you go. [laughter]

Anna: Thank you.

Zibby: I like how you threw yourself in the mix. Another way that you made this book so relatable, literally starting by talking about whether or not you're getting your period. I'm like, oh, okay, wait a minute, this book is not what I thought it was going to be. She's open. The author is open and talking to me like a friend. Now she's going to tell me a story and teach me. It's like when a great teacher stands up. Of course, that's probably what you're doing. You're getting your PhD and everything, right? Are you trying to be a professor? What's the goal there?

Anna: It's so interesting when you said that comment about textbooks earlier because I agree in many ways that they can be a little boring, is the only thing. I definitely respect them for what they are. They're such important tools for all of my academic colleagues who do want to be professors right away.

Zibby: Yes. I'm sorry.

Anna: No, but for me, I'm actually not. I'm much more interested in public intellectual work. That's why I wanted to produce a book that was very readable, very accessible while also being a tool that could be used for education, but just in a way that's more fun and that you can connect with. It feels personal. I believe that black feminist theory, gender theory, critical race theory all were meant to help us better understand our world and to survive our world and change it. It wasn't meant to be exclusive or kept within the academy. I am grateful for my time in the academy. I am definitely a nerd. I love my degrees. I loved doing all the research to earn them, but it isn't where I necessarily want to stay for now. I'm much more interested in talking to general audiences about what they think and contributing to current conversations because so much is happening so quickly. Sometimes when you're an academic and you're only talking to other academics, you feel like you're kind of missing out because it takes years to develop certain articles and get them published. Then it's only other academics who are reading them. That's just not currently what I'm interested in doing. Maybe down the line I would become a professor. I love just talking to everybody about what they think. That's what I'm most excited about with the book, seeing what all these different people get from it and what they gain from it.

Zibby: Oh, my gosh, you're going to have the most amazing conversations. There's so much in here. I was hoping I could just read this one point that I particularly loved. It's all the way at the end. I'm sorry. It's part of Our Lives Will Not Be Erased. You said, "I cannot fully express just how much hurt and frustration the erasure and misrecognition of women and mothers, especially black women and mothers, causes me. In my own life, I've experienced others demeaning me and questioning my abilities simply because I am a black woman. How many times have men threatened my sense of safety, hollering at me from their cars? How many times have I heard I was only given an opportunity because of the color of my skin? How many times has another person's looks or comments tried to make me question my worth? I cannot say. There have been too many." I'm reading one more paragraph. I can't stop. Sorry. "I also cannot tell you how many times people have been surprised by my intellect and my successes because they assume I am dumb and that my biggest accomplishment was marrying my husband. My own work has often been hidden behind his, not for lack of his appreciation, but because we still live in a world where women of color are not fully seen." Then you say, "Now that I'm a mother, this erasure takes place on new levels. I have stood at events right next to my husband while he was congratulated on the birth of his son." Then you keep going on and on from there. Wow, that's super powerful stuff right there. That's amazing.

Anna: Thank you. I think so many women relate to it and can feel -- I would love to hear your own experiences of that as well. So often, we're taken for granted, especially moms. It's this weird balance of everyone expecting us to do everything and get everything done. If we don't, then we're blamed for it, but we're never thanked for being the ones who are running the operation in so many different ways. Of course, that's different in different families. In general, women are underappreciated. We see this in the way that we're treated and lack of safety and general toxic masculinity. I think part of it was adding my own personal experience to that so that people understand why this book mattered so much to me, but also to be someone who's saying, I see you. I see all of us who are going through this. I hope that this book can be a part of changing that.

Zibby: Even your dedication, I started getting the chills. Wait, hold on, I have to read this too. Then I'll stop reading.

Anna: No, I love it. This is so fun. [laughter]

Zibby: You said, "This is for all the mamas. You deserve respect, dignity, and recognition. I honor you. I celebrate you. I see you." I don't know if you were talking to me, but I took it.

Anna: Yes, please do.

Zibby: I know this is geared -- well, it's not geared towards black mothers, but it's mostly about getting the facts out into the world so that they are seen in a way that they have not been in the past.

Anna: It truly is for all the mamas, though. I actually define motherhood even more broadly than biological motherhood. Patricia Hill Collins calls mother work the kind of work we do that's caring for others, the way we're bringing others up. Teachers are doing mother work, doctors, nurses, so many of our essential workers. It is definitely a celebration specifically of motherhood, very specifically of black motherhood, but also for all of those that are doing work on behalf of many and who feel unappreciated, feel unseen. It's our time. We need people to give us the appreciation that we deserve. There is nothing that they're going to lose by giving credit where it's due.

Zibby: Ooh, maybe there's some tie-in here with my podcast. It's our time. I love how you say that because that's also what I try to say about listening to this podcast. I don't mean just moms. There are caretakers in so many ways, shape, and form. Not that you even have to be a caretaker, but mom itself, the word, is so limiting, whereas it's such a broad spectrum of people caring for others these days. Content is for whoever wants to ingest it. I believe it'll find the right home.

Anna: I'm excited about that part of the conversation too, just thinking of the different ways and the different mothers. This is especially common in black communities, communities of color, the mothers that you have even outside of your own moms because of this it takes a village to raise a child mentality and practice and tradition that is so beautiful and wonderful. It's very western to do this as an individual journey that everything falls on the one person and that they shouldn't ask for help or they shouldn't admit when something is hard for them. Even when we're having conversations about postpartum depression, so much of that can be avoided or helped and supported if we have more people around that central figure, but also if we just see her. In so many cases, it's going to be a woman who is not seen, who is not given the supports and resources that she needs. We can really change that and make it easier. It's better for our kids and better for society. I'm all about the more you support women, the better society and communities do. I also hope that it contributes to that as well. I have a lot of goals for the book. We'll see how many I accomplish.

Zibby: You should. I believe it will accomplish a lot. Let's talk about these three mothers in particular. You probably know more about these women than anyone, as you spell out so clearly. Even things like the date that they were born is two different dates for certain of the women for their birthdate and just so much conflicting research because they weren’t even deemed worthy of recording in a way. You went and must have torn apart every library and every website looking for everything you uncovered. First, I want to know about your research and how you did that. I really want to know -- maybe, let's talk about this first, if you don't mind. These three women who went through so much and overcame so much, it's unbelievable, yet they produced these leaders. Is there anything as a main takeaway for other mothers if you want to raise a leader and someone who can speak their mind and effect change in society? Is there anything you feel like they did that we can all do?

Anna: Wow. There is so much that I could say to answer that question because, of course, the book is filled with those lessons on how did they do it day to day with all of the challenges that they were facing? I like to celebrate their differences even more than what they had in common because of this notion that we try to categorize black women as if we're all the same. A big part of the book is celebrating how different all three of the mother's approaches were to accomplishing something that in the end, we have these three incredible men despite the many differences in their backgrounds. One thing I think that they all had in common was this combination between both vulnerability and bravery and the way they saw themselves and what they were going to teach their children about themselves and how that allowed their kids to understand humanity better. To break that down a little bit, so often, moms feel that we have to put on this brave face all the time. We can't let our kids see us cry. We can't let them see that we're struggling to do something because we feel like we have to be those superhero moms.

In all three of these cases, they were willing to say, hey, this is difficult for me. Alberta King was constantly worried about Martin Luther King, Jr. going out into the world. That was very real for her. That was her son still. No matter what she wanted him to accomplish, no matter how she had faith in what God's plan was for him, she worried about her baby. We see it with Berdis Baldwin when she loses her own father. She cries in front of her son. She is able to show some of the things that are difficult for her. Louise Little, again, filled with examples of her showing that things could sometimes be very scary. What do you do in those moments where you have sadness, where you have some fear, where you have some worry? You continue to push forward. You ask for help from others. You form communities around you. They all were examples of that balance, vulnerability and strength and being this whole human being that I think allowed all three men to have a really deep understanding. One of the reasons they were all three incredible orators and organizers was they had an understanding of humanity that others did not. I think a big part of that was that their moms were very willing to be honest with them about their own human condition.

Zibby: Okay, I can do that. [laughs]

Anna: It's hard, though. It really is. My son's still really young, so I'm not sure he's going to remember all of my own emotions and my journey of being his mother. I think that honesty is crucial, especially with sons. When they see women in their full humanity in true light, it can make them better human beings.

Zibby: That's great. Nothing like getting some parenting advice here in the midst of --

Anna: -- I want all your parenting advice.

Zibby: Oh, my gosh. If your kid has a rash, I will know what it is. I have four kids. I feel like I need to set up shop, a little corner in my pediatrician's office and just be like, why don't you just come through the triage center here? I will let you know what's going on. Then you can leave.

Anna: That is hilarious. That would be actually really effective for hospitals. Just have some moms sitting there ready to talk to new moms.

Zibby: Right? Maybe I should do that. I actually am on the board of something called the Parenting Center at Mount Sinai Medical Center. It's a lot of parent education and all that. I've never thought about just plopping myself down one day and being like, all right, listen. [laughter] Let me tell you how it is.

Anna: He's fine. They're fine. I love that.

Zibby: They're fine. My biggest parenting lesson that I feel like I probably say too much is that you don't have as much influence as you think you have. I think that my kids, each one is born the way that they are. They're all so different. Their genes may be the same, generally, but they're completely different people. I just am here to watch them. With my first kids, I was on top of them. What are you doing? What are you doing? How can I make you better? At this point, I'm just like, look at this. My son's redesigning his room. How about that?

Anna: The creativity, how wonderful. To that point, with these three moms, they had several other kids. We so often only talk about their famous kids, but that's another really cool way to see even how they approached their different kids and their personalities and what they wanted to do with their lives. I think we can gain a little bit from those lessons as well.

Zibby: There was this show that I used to watch. It was only on for one or two seasons. Then it was canceled. Now I'm going to forget the name again. Something like Bob &... It was about when JFK and his brother Bobby were boys. It was trying to show, what did you see in them when they were boys? It was a lot about their mom and how she was raising them. You should try to dig it up.

Anna: I love that. That feels like it's up my alley.

Zibby: It was so good. Oh, it's called Jack & Bobby. I feel like the only person who watched it. I think maybe I was pregnant. There was some reason I was home watching a lot of TV. It's sort of the same theme. What was it in their childhood? That's not exactly what you were doing, but it's always so interesting to look back and see, could this have been the influence? What about this? How did she handle that? Or is it in spite of your parents that you end up becoming a leader?

Anna: That's definitely the case sometimes, for sure.

Zibby: Go back to how you dug up all this information and wrote this book. Your son must be one and half or something at this point?

Anna: Now he's fifteen months.

Zibby: Pretty close.

Anna: Full-on toddler mode. He's just running around and talking and has some declarative statements. We have no idea what he's saying, but he's really emphatic. [laughs] It's a really cute stage.

Zibby: How did you do this whole book at the same time? You must have done a lot of it before. Tell me about that.

Anna: I started the research before we were expecting my son. Started with my PhD program. Definitely, the journey of becoming a mother while moving through the different stages and then having my son while I was editing the book gave me this very rich, deep, personal connection to the three women that I'm really grateful for because motherhood can be an incredibly scary journey as much as it is really exciting. Especially for black women in the United States, seeing what they were able to push through, but also the way they were able to transform their communities to better meet their needs brought me incredible inspiration. In terms of the nitty-gritty of actually finding all of this information around their lives, it was really hard. I say in the book that it was finding a needle in a haystack. Even if you just take one paragraph, you'd have to break it down into almost each sentence that I had to find a different fact in order to complete that one paragraph because information about them was so scattered. Then there were conflicting documents on what one person said versus another scholar versus all of these things. That's what adds to the complexity of their humanity. It's definitely a challenge that I appreciated.

What frustrated me most was how little there was out there because there's so much more about their lives. I hope maybe the families will be more willing to speak about them now. One of the problems -- maybe it's not a problem, but it's a challenge. They wanted to protect their moms. These are three families who had been through so much scrutiny, so much inquisition from different sources, whether that was scholars or journalists, etc. I definitely felt their need to keep this person who was so important in their life guarded from that kind of scrutiny. I am excited, though, now that they're able to see what the product was and what I wanted to do all along that they feel proud of it and they're happy with what I was able to do. Hopefully, that will allow us to hear even more stories about these three women. So much of it was going through all of the men's works first, then anything that people had written about the men. There is so much. It's incredible. Every single year, there's a new book about one of these men, which I find incredibly brave by these writers because what else is there to say? I don't know how brave they are to go in and say, I have a whole new thing about these three men that we've already learned so much about. There's nothing wrong with that. I just hope we can have multiple books about the moms as well and taking them, like I said earlier, from the margins and bring them to the center. If there was just a small mention, I would take that.

I had to really go away from my computer. I had poster boards all over my walls with these really huge timelines. I was filling them in with Post-it Notes. Then I could see where I had really big gaps which actually tended to be towards the beginning of the women's lives before they were married, before a man made their life worth recording, really. Unfortunately, that's kind of how it appeared and what it symbolized when I had this huge gap between maybe they were born this year, but we know for sure they married their husband that year. This is when they had their famous sons. Going back and filling that in with historical context and going really on a deep dive into Grenada's history and Deal Island's history and Atlanta's history, that's how I just filled it all out and took little parts where other people had said -- Maya Angelou had described Berdis Baldwin, so finding her name in one of Maya Angelou's speeches and learning that she was really short and that Maya Angelou had to bend to half her height to kiss her on the forehead. That was how it all came together. Then I called different historians around the country. I was also able to work with some researchers at different sites who helped me find birth certificates and marriage certificates and doctor's notes, even, from some scholars who studied the men and had archives that no one had asked to see before about the moms. They just shared those with me. It was an incredible journey, really difficult, but also a really beautiful one at the same time.

Zibby: Wow, and a fabulous final product. I feel like, and maybe this is already in the works, but shouldn't this be a three-part series on HBO or something like that?

Anna: I would love that. I really would. There's definitely some interest in it. I do have a film and TV agent, so we will see how that goes. The way I picture it is Netflix limited series, maybe two episodes for each mom, and just getting to better understand, again, what we were saying at the beginning, the context of US history. That's the thing that really connects them because all three of these moms never met each other. Their sons would meet each other eventually, which I think is really a beautiful part of the book as well. To see how something might happen nationally and then you get the scene through that mother's life I think would be really beautiful. We'll see what happens.

Zibby: Okay, fine, it won't be three parts. I've now expanded my order to perhaps a six, seven, or eight-part miniseries.

Anna: Even a musical. I think a musical would be beautiful.

Zibby: Musical?

Anna: Yes, like a Hamilton but where the characters are actually people of color. That would be cool.

Zibby: I miss the theater so much these days.

Anna: Me too.

Zibby: Oh, my gosh. I didn't think I would miss it so much.

Anna: Then you can't go. You're like, I want to go so badly.

Zibby: Right? Anyway, wow, that would be really interesting too. So much you could do. I feel like I want to pause life right here for a minute, fast-forward twenty years, and see what you're doing. I feel like you're going to do really amazing things in the world for so many reasons. I'm just really excited to watch how you end up harnessing your intellect and hard work and perspective and empathy, all of it combined to effect change.

Anna: That means the world to me, Zibby. I really appreciate that. Hopefully, we'll have more conversations. Twenty years from now, I'll have another [indiscernible/crosstalk].

Zibby: When you are whatever you want to be, whether you're the president or whatever -- do you have giant aspirations, or not really?

Anna: It's so crazy because in many ways, I'm living the dream that I've had for so long. I wanted to write books and travel and speak about them. The travel aspect is definitely being hindered by COVID right now, but that's okay. I'm getting to travel from my living room, which is a lot of fun. I really did just want to produce my writing. I do fiction and nonfiction. My next one is going to be a novel that I'm finishing up and hopefully will be able to pitch this year. Just talking to people about it and getting everybody excited about things that can be complicated and theory that people feel maybe is overwhelming and that pushes them out of the conversation but that actually brings them into a welcoming environment where we can sit and talk about things that are affecting us as a nation. We'll see. Maybe that turns into a TV show at some point. I don't know. I'm excited to see. It's fun. Hopefully, maybe having some more kids. I think that's a huge part of my journey as well. I don't know what the future holds, but I'm really enjoying the moment. This is where I've wanted to be for a long time. I cannot believe the book is now out.

Zibby: So exciting. Enjoy it. I didn't mean to not give this moment its due. I was just curious.

Anna: No, I appreciate that. I'm excited too to see what happens. What about you? Where do you want to be?

Zibby: I just want to keep doing more of what I'm doing. I want to just expand all the things I'm starting. I don't know. I just want to see where it all goes.

Anna: It's such a good position to be in where you're like, I love this. Let's just do more of this on bigger levels, bigger scales.

Zibby: If I could just replicate myself, that would be good. [laughter] Do you have any advice for aspiring authors?

Anna: Wow, yeah. For me, I always talk about the fact that it was not an easy journey, necessarily. I am young, but I also applied to PhD programs four times. Didn't really find where I wanted to be. Didn't get into all the programs I wanted to get into. It was really sad. Every time I got these rejection letters, I was like, but everyone told me that I had done what I needed to do to make it to the next step. I've done all the work. Then it just was perfect where I ended up and being at Cambridge and having the support of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and being able to compete my PhD within three years. I had become really obsessed with doing an American PhD program that was going to take me seven years and when I wasn’t getting into those programs, felt really dejected and felt like maybe I was not understanding what I was supposed to be doing with my life. Then now fast-forward to finally getting into a perfect program and having my book out. You just have to really push forward past those rejection letters. There's going to be so many of them. Even if you want to not necessarily -- self-publishing is a different route. If you want to work with an agent and you want to get a book deal, some agents aren't going to work with you. They're not even going to reply to your query letter.

You'll find the ones who believe in you. Then from there, the ball just keeps rolling. It's probably very cliché. I think everybody says this. It's so much easier said when you've accomplished the thing than when you're in the middle of the struggle. Definitely, from somebody who received a lot of rejection letters and who, at times, felt like maybe I wasn't doing what I really in my heart felt I was supposed to be doing, just to keep pushing, but also being understanding with yourself. Then with the novel that I'm hoping to pitch this year, I've been writing it for four years. It's a long, long process. I remember other writers telling me that at the beginning. I didn't really believe them. I was like, sure, you maybe had to wait that long, but I'm going to have this book out so much sooner. I'm on my sixth round of edits. It's getting closer and closer each time, but it is a journey. Just stick with it if you really love it. It's definitely worth it once you're able to show the world your work.

Zibby: Perfect. Great. Anna, thank you so much. Thanks for the coming on the show. Thanks for your amazing book and all of what you have to teach in so many different ways.

Anna: Thank you so much, Zibby. I really appreciate the time.

Zibby: Take care.

Anna: Bye.

Zibby: Buh-bye.

Laura Tremaine, SHARE YOUR STUFF. I'LL GO FIRST.

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Laura. I'm so excited to welcome you to "Moms Don't Have Time to Read Books."

Laura Tremaine: I am so excited to be here, Zibby. Thank you for having me.

Zibby: As I was just saying before the podcast, I feel like I know you because of your amazing podcast and your new book, Share Your Stuff. I'll Go First.: 10 Questions to Take Your Friendships to the Next Level. The best part about this book was all the stuff that you shared, I think. I just wanted to know more and more about you. I was like, forget the questions. Tell me more about Laura. [laughs] Congratulations on the book.

Laura: Thank you very much. I'm super excited, my first book even though I've been writing for all this time. I feel like, finally, I get to have something I hold in my hands that's not just on the internet.

Zibby: That must feel amazing, right?

Laura: It feels amazing. It really does.

Zibby: Tell me about the inspiration for this book. What made you write it? Why did you package it up this way with questions for other people to ask? It has a little self-help component to it in the midst of the memoir, I would say. It's an assortment of bullets at the end and ten funny things or things you wouldn't know about you and then questions you can ask your friends. Tell me about the format choice.

Laura: It's funny because I always pictured and always wanted to write more traditional memoir or at least personal essay. I thought that was the more literary, sophisticated thing that a person should write. I did try to do that. It just felt forced. It felt like I was trying to be a sophisticated writer when actually, everything flowed a whole lot easier when I just did what I really do, which is just share my story and talk the same way that I would if I was talking to an audience on my podcast or on Instagram or something like that. When I changed up my mindset around it and stopped trying to be an essayist and decided to share the way that I am comfortable sharing, it just came out in this format. On my podcast, which is called "10 Things to Tell You," I ask a question every week. Then you're supposed to answer the question. They're often either introspective or you're supposed to take it to a friend and do it as a get-to-know-you conversation starter.

It made sense to structure the book that way. I came up with ten questions that, first of all, I actually wanted to answer, but also ten questions that I felt like come up a lot on my podcast or from my audience that they want to hear more about from me or from their friends or that they want to share about themselves. I came up with these ten questions -- some of them are deep; some of them are not so deep -- and just structured the stories that I wanted to tell within the format of those questions. Instead of trying to make this meaningful, thoughtful, essay, I really just wanted to tell you about this story that happened in my life. It just came out that way. It felt very natural. It felt much more natural. As I've gotten older, I've realized that what seems to flow is what you need to go with instead of trying to be this other thing. That's how I got here.

Zibby: That's amazing. The story that I've actually already retold now twice is when the scary van pulled up at the house when you were inside. You were so scared. The neighbor comes walking down the street. You throw yourself into his arms. Maybe you should tell the story, a synopsis better that I just did, and how that played into your anxiety, which you also talk about in a really impactful way throughout this book starting in the very beginning and coursing through from your hair-pulling to all these things that were manifestations of your anxiety. Then this one moment, I felt like, was the pinnacle of everything you've ever worried about, and the break-in, but we can talk about that after.

Laura: It was a huge moment in my life. I was a super anxious child. I write about that a lot, my childhood anxiety. I talk about that online. I pulled my hair out. I had bald spots. I had a lot of coping mechanisms. Growing up in the eighties in a tiny town in Oklahoma, there was no help to be had. I didn't see a therapist. I was just a little quirky kid. What it really was is I had a lot of anxiety and a lot of ways that that manifested. I was also a latchkey kid. Both of my parents worked. I was at home alone for hours every day after school starting in the second or third grade. We lived out in the country in the middle of nowhere. I would ride the bus home and then be home in the woods for hours. I was a little bit older when this story happened. I put it in the framework of the question. The chapter that this story falls in is, what are you afraid of? I feel like when you ask someone what they're afraid of, what their deepest fear is, who wants to talk about that? Why are we sharing about this? It seems like such a scary thing to talk about. For me, when I talk about things that I'm afraid of, it makes them less scary. The more that I can drag this dark thing into the light, it makes it less scary to me. It takes the power away from it. When I was a little kid and I was at home alone, the creepiest, most after-school special thing happened where a rusty white van pulled into the driveway where I was playing outside. We were out in the country. I just knew it deep inside my soul that there was something not right about it. Spoiler alert, nothing happened. I was not kidnapped, by the way.

Zibby: You're still here. You're here, so it all worked out okay.

Laura: It all worked out. It really did kick off, for an anxious child, the scary thing that happened that I just intuitively felt like was an evil thing. I guess we'll never know because, again, I wasn't kidnapped. It really did kick off a lot of things in me. I became really obsessed with true crime after that. I was young. I was pre-teen, probably, when that happened. Into my teenage years and into my college years, I got really into true crime before that was as popular as it is now. I really got very fearful. It was where my anxiety took a turn. Also, a deeper layer to that story that nothing ever actually happened in, but a deeper layer to that story was I told everyone around me that there was something evil about that van. Again, I was eleven, twelve. I'd been staying home for years. Things had happened. People had rang the doorbell. People had stopped by the house, strangers. I had never felt this kind of deep inner fear. It really bothered me when my parents or my siblings, no one believed me that there was something different about this situation. I felt like in that moment not only did I have a real twist and turn towards -- my fear took a real turn. Also, maybe that's the moment when I kind of became a self-advocate or something. I realized no one is going to believe me just on my word of it, just on my own intuition.

It really changed my life. After that, I stopped staying home alone. I would go to the library after school or other things. I had to make all those adjustments and all those changes myself. I had to be like, okay, if no one's going to believe me that I'm in danger out there in the woods, I'm going to have to take it on. I talked about that story in my family. It's sort of a family lore story. We still joke about it. No one in my family, still to this moment, believes that there was anything wrong with that van. For me, when I sat down to write my book, it was one of these primary stories of my life that I wanted to share. When I'm thinking of the ten stories I want to share in my first book, it was one of the major ones. I think that this happens to a lot of us in our childhood. We have this pivotal moment. Maybe it is a truly tragic moment or something really huge that you can point to. Maybe it's a nothing story like mine. A scary van pulled in. A scary van pulled out. That's the story, but it was a big thing for me. I wanted to share it also as a way to give the reader permission to take those kind of "nothing" stories and say, yeah, this has some weight for me. It doesn't matter if no one ever understands why, but this was a real moment for me.

Zibby: I think that's something just so relatable, when you have any sort of fear or doubt and you can't get people on your side about it or people minimizing the worry, which never helps. I'm so worried about -- oh, you'll be fine. You'll be fine. That makes it worse. That always makes it worse.

Laura: It was a really big deal to me that I wasn't believed. It also sort of set me on this path of listening to my intuition or not. No one used that kind of language with me back then. Really, it is a thing of, you have to trust yourself. If you sense that something is not right here, you have to believe that. You have to go with that.

Zibby: And PS, that's how you got all that time in the library. Perhaps that's why you even wrote this book and why we're on the Zoom together.

Laura: Thank you for connecting all the dots. Thank you. Thank you.

Zibby: Anytime. My pleasure. I also loved all your delving into your past relationships and how each chapter, not every chapter, but many chapters had little scattered Hansel and Gretel-type crumbs of your past relationships from the pastor to coercing your husband to marry you to your first boyfriend, all these broken hearts, everything. I felt like the way you unveiled your relationship history was very -- I almost felt voyeuristic, like, ooh. [laughs] I'm snooping here into her private life. I found it just so entertaining and awesome.

Laura: Thank you for saying that. I will say, that is something I'm, I don't want to say embarrassed about, but I have some vague vulnerabilities that I'm a forty-one-year-old woman, married happily, mom of two, and I am still writing about ex-boyfriends and things like that. I got to the end of the first draft and I was like, did I write too much about my exes? My publisher was like, "Maybe."

Zibby: Did you take some out? Is this the edited-down version?

Laura: Yes. [laughter]

Zibby: I don't know. I really like those parts. I feel like once we're all married and boring and all the rest, it's nice to hear about what the before was. It's similar to how I feel about meeting brothers and sisters of friends I made as grown-ups. Whereas when we're kids, you know everybody's family. It just gives a context to everything else. It gives more context to a person to hear about how they got where they are.

Laura: It does. The same as the white van story being a childhood story, in some ways, those early relationships, your first love or your first heartbreak or the person you almost married but didn't, all of those people, if you're lucky enough to have had such a trail, then they do matter to your life. One really bad heartbreak will probably affect how you interact in your next relationship or whatever. There is a connection to all of these things. After a certain age or after you've been married a certain length of time, you're not supposed to talk about that anymore. You're supposed to think that that is all dumb and young, immature stuff and doesn't really matter. That's just not true. Those relationships meant a lot to my life. They definitely affected the relationships after them, which then of course became a marriage. I don't think you should dwell on them. There's obviously an unhealthy, toxic place you can get to with fixating on past relationships. I have tons of girlfriends, and like you said, I could hear about their exes all day.

Zibby: Right? It's so juicy.

Laura: It's funny. It's interesting. Tell me all the ex stories.

Zibby: Totally. Plus, you include so much about what it feels like to be a transplant in LA and making that into your home and your whole blog, which of course is how you have turned this whole thing into the thing that it is. In fact, I want to hear more about that. You started the blog, Hollywood Housewife. Did I get that right, Hollywood Housewife?

Laura: That is right.

Zibby: By the way, do you know the author Helen Ellis? Do you know who she is? Have you read her work?

Laura: Is she the American Housewife?

Zibby: Yes. She wrote American Housewife and Southern Lady Code and has a new book coming out. I think she's from Kentucky but lives in New York City. I feel like you jumped off from different places and landed on different coasts, but you're both very funny and witty. If I were still doing all my events, I would do one with the two of you because I feel like you'd have such an interesting conversation. Maybe I could just introduce you. I feel like you would be friends.

Laura: I would love that. She has been in my to-read stack for ages because I also sort of felt like maybe we would have something in common. I haven't gotten to her yet, but I will. I think I will.

Zibby: I don't know why I'm plugging another author in the middle of our interview. I'm sorry. I'm just trying to connect you, and not in a negative way.

Laura: No, I love it. I love it.

Zibby: So Hollywood Housewife, you start the blog. How does the blog become the podcast, becomes the book? Tell me that whole story.

Laura: There are a lot of steps in between. I started the blog when my daughter was just a few months old. It was 2010. I'd been reading mommy blogs in the years that I was trying to get pregnant and then while I was pregnant. The internet, not the internet as a whole, but blogs and personal sharing and all of this kind of thing was still a real novelty. I loved it. I've always felt like I was a writer in my soul. This removed all the gatekeepers. There was no publishers. You could just share your stuff online. I was obsessed. I actually started the mommy blog because that's what people were doing. I didn't have a whole lot of interest in actually writing about motherhood. I still don't have a lot of interest in writing about motherhood in general, but that was sort of the avenue for me to be able to write immediately. I started that in 2010. I was able to build a little bit of an audience. A lot of the feedback that I got from people was that they loved reading blogs like I did. They loved reading my blog, but they would never share themselves. They just wanted to read other people's stuff. They wanted me to keep doing it, but they would never.

That's a very strange, backhanded compliment. I think they actually did mean it as a compliment. Actually, what they were saying was they would never be so tacky as to put themselves on the internet. I just kept receiving that message, some version of that message, over and over. Then when social media started, there was all this shame around people posting selfies. I just kept seeing this message of women who liked other people to share, but they could never share themselves. It wasn't because they were deeply insecure or anything. There was all these reasons, these cultural reasons. Maybe there was some insecurity. It felt passive-aggressive. It felt like people needed permission to share. They didn't necessarily want to be on a stage, but they did want to share themselves. They did want to have connection with other people. My time at Hollywood Housewife, writing that particular blog which was very family focused, as my kids got older and I also started to tire of the name and the branding, it didn't really fit. It sort of was meant to be tongue and cheek during the Real Housewives franchise, that boom. Then it started to be like, I'm sort of embarrassed to say this, that this is the name of my blog.

I started to phase that out and decided to close that actual blog. By that time, I was a cohost on a podcast called "Sorta Awesome" which I had kind of done as a favor to a friend, to be honest. I didn't know anything about podcasting, but I was like, fine, whatever. I just loved it. As you might have experienced, I ended up loving using my actual voice. I loved having the good conversations. I had been trying to make this writing go in a more serious way. I'd been trying to use the blog to do that. When I closed the blog and started talking is when I felt like I really found my voice. It then became so much easier for me to write because I didn't have all these hangs-ups about the perfect sentence structure or anything. I felt like when I was actually talking and I was getting a response, I found a groove. I took what I had learned during that mommy blogging time of just seeing how lonely women were on the internet -- they were turning to the internet. They were turning to blogs and then eventually social media to watch women share themselves, but they weren’t actually sharing their own selves. They didn't know how.

I hosted a few of these challenges to get people to share. What I learned -- this is still true to this very moment. If you give people an assignment, if you're like, we're all going to share this thing, we're going to share our favorite reading chair, we're going to share a selfie, we're going to share what we learned this month, whatever, give them any kind of assignment, people will share. They feel a permission when they say, well, I'm participating in this online challenge, so I can share this. Whereas they would never in a million, gillion years just say, hey everybody, this is my favorite reading chair. They just wouldn't do that. If they have this thing that they're participating in, they will do it. They want to do it. I loved that. I'm like, great, I will give you all the prompts. We will do all the prompts if you will share, if it will get you sharing, if it will get all of us sharing. I had done this challenge called 10 Things to Tell You. That's what I called the challenge. It was so successful and made me so happy that then I decided to make that a weekly thing and make that be a podcast because by then I had discovered that I loved podcasting. The podcast was called "10 Things to Tell You." The challenge online that I still do is 10 Things to Tell You. Then when I pitched the book, I pitched it as 10 Things to Tell You, but it became Share Your Stuff. I'll Go First. I like that title better.

Zibby: There you go, or so we're going to tell the publisher. [laughs]

Laura: That's right.

Zibby: I love the title. I would've loved the other title too. It's great. It just totally tells you what type of person the author is and the willingness to be open. Then that's when people want to be open back right away. You go first, we're in.

Laura: Exactly. I hope that it gives people permission. There is a tiny bit of a self-help element to it. I'm not an expert in that. I don't have any degree. I hold all that stuff lightly. I enjoy self-help books and stuff myself. I love them. I love to talk through what I'm learning and how I'm growing. That comes out in the book a lot when I'm trying to encourage people how they can think about this question or this prompt. I also just want to be really clear with everyone that this is no expertise. I'm a self-help hobbyist.

Zibby: When I mentioned self-help in the beginning, I didn't mean to scare anybody that this is a true expert. I hope that you didn't take it -- the stuff with genre these days, there's so much overlap. I feel like anything that can help somebody else I consider sort of self-help.

Laura: Totally. I'm all about self-help. I love all of that stuff. I think this is categorized as self-help or motivation or some kind of thing like that, but a lot of it's my personal story in the book.

Zibby: Personally, I find that a lot more compelling than more research. Research is really interesting as well, but not if you're trying to spark a conversation, perhaps. Do you have more writing aspirations? What's coming next? What's your game plan here? Do you have one?

Laura: I do. This is a two-book deal. I am starting a new book in 2021, sometime. I don't totally know the angle, but it will be in the same genre, I guess we'll say. I do love mixing this personal essay with other nonfiction elements. It's a funny hybrid that seems to have sprung up out of internet culture, speaking directly to the reader but then also sharing personal things. Then like I said, it feels comfortable for me. As I try to hone my writing skills on and on, I do hope that I'm maybe writing something different in ten years. It has been a process to not be embarrassed to be a blogger, to not be embarrassed to be a self-help hobbyist, to get where I am and own it and be like, this is actually my sweet spot this year and where I am right now. Maybe I'll be a serious writer in the future, or maybe this is what my talent is. That's been a process. I think that was a process all through my thirties and as we slide into my forties, to be like, actually, what is prestigious anymore? It's kind of just what connects with people.

Zibby: Only one book a year can win the National Book Award. Let someone else win that book award. In other words, there are authors who, that's their go-to, is that style of writing and the obsession with form and intricacy and sentence and all of that. Let them have that if that's their thing. That might come as easily to them as you speaking from the heart comes to you. Everyone can tell when someone's trying to be something that they're not. This is how I felt in business school. There are people there who are dying to get jobs in marketing. I was like, oh, marketing is a fallback for me. This is how I knew I didn't really want to do that. It's the same kind of thing. The people who really want to write literary fiction can write literary fiction. It doesn't have to be you. That's totally cool. That's my philosophy.

Laura: I'll love to read it.

Zibby: I get it.

Laura: I love to read some really highbrow things. I love it. I feel smart. I'm amazed that people can do it. It's taken me a long time to be like, but I'm not going to do it.

Zibby: That's okay. You wrote a whole book. It's a great book. It makes everybody who reads it want to be your friend. How cool is that?

Laura: I hope so, Zibby. Thank you for saying that. Let's hope so.

Zibby: I think so. Now that I've pinned you as some sort of an expert in some way, what advice do you have to aspiring authors, perhaps aside from don't try to -- well, that was my advice. Don't try to win the National Book Award on the first try. Anyway, go ahead. [laughs]

Laura: I think you should try different avenues to find your voice. I knew I was a writer, but when I was writing -- they say you're supposed to write every day to become a better writer and everything. I did that. I wrote every day on my blog for years and years. Of course, it was an amazing discipline. I did learn a lot in writing for an audience by doing that. I had to take a few years and do something else, which was podcasting, which was using my physical voice. Then when I came back to the actual page, I was a much stronger writer. I don't think that, for aspiring authors, you have to be scared of taking some time to do something else, to try painting, to try singing. You're not losing your writing muscles when you go to try to find yourself or try to find a way to express yourself with a different medium. If writing is really what you want to do, it will come back to you tenfold.

I really worried when I gave up my daily writing habit that I was sort of giving up that dream. It was the complete opposite. I don't want to go on a tangent here, but I tried to get a book deal with my blog and all of that kind of stuff. It didn't go anywhere. I didn't get it. When I closed all of that up and I thought that was the end of a chapter, it was like the opposite was true. I needed to go do this other thing for a couple of years. Then when I came back and I was like, I really want to be a writer, I was shocked at how much more easily it flowed then from just taking the years of the disciple, but then taking the time to do something else. I hope that that makes sense to an aspiring writer because I know that it's scary. I definitely did not know that in the moment. This is me in hindsight, but it's really true.

Zibby: I love that. I totally relate. That's awesome. And relate to how much fun podcasting is and all the benefits. It's a writing-adjacent activity in a way.

Laura: It is. You're still having to express yourself articulately. It is. It's a thing.

Zibby: I'm hoping being articulate is not a prerequisite every day because I'm struggling to string sentences together today, but in general, self-expression and all that. [laughs] Laura, thank you so much. Thanks again for this awesome book, Share Your Stuff. I'll Go First.: 10 Questions to Take Your Friendships to the Next Level. I'm just wishing you all the best. I'm so excited you came on my podcast.

Laura: Thank you. I loved it so much. I love that you're holding it. It makes me so happy. Actually, can I take a picture? Is this too weird?

Zibby: No, I love that.

Laura: I'm just going to look so meta. I'm doing it anyway. Ah, you're so cute! Thank you for having me. This was super fun.

Zibby: This was super fun.

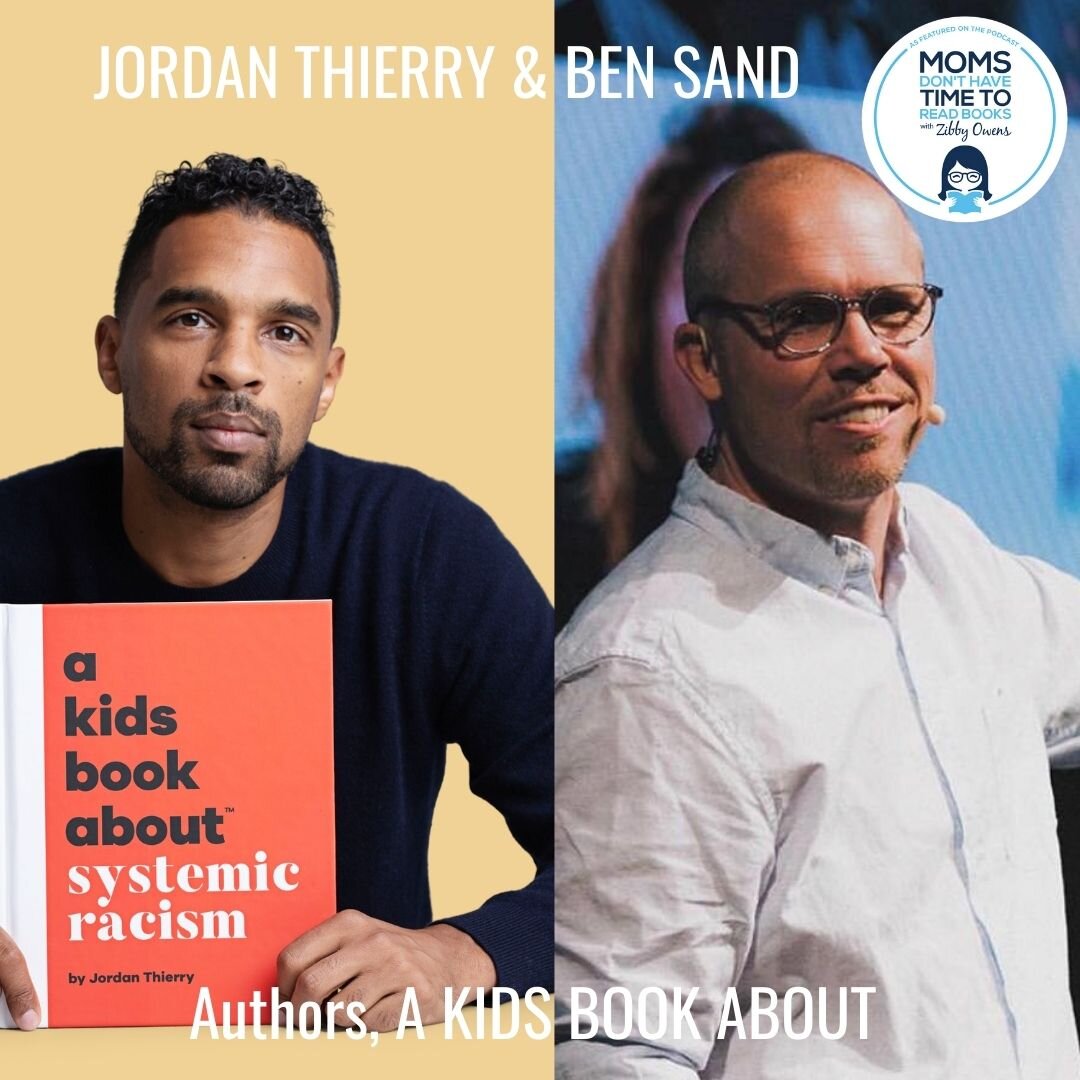

Jordan Thierry and Ben Sand, A KIDS BOOK ABOUT

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Jordan and Ben, to "Moms Don't Have Time to Read Books." Thanks for doing this interview together.

Ben Sand: Absolutely. Thanks for having us.

Jordan Thierry: Thank you for having us on, Zibby.

Zibby: It's my pleasure. Ben, you're the author of A Kids Book About White Privilege, and Jordan, A Kids Book About Systemic Racism, in the new series of kids' books which are fantastic, educational, inspiring, all the rest. First, how did you two end up contributing to this series? Jordan, take it away.

Jordan: I can go first. I know the founder of A Kids Book About, Jelani Memory, from youth. We played basketball together growing up. We had done some work together as adults. He reached out. He wrote A Kids Book About Racism. We had touched base and were thinking about a topic for me to write. Then after the murder of George Floyd, we reconnected and decided that A Kids Book About Systemic Racism would be a really great topic to help people understand why these racial injustices continue to thrive in our society that explain that phenomenon beyond the individual one-on-one racism, as I think a lot of people like to think of racism, but looking at the systems that allow these things to continue.

Zibby: How about you, Ben?

Ben: In a way, similar. Jelani Memory, the CEO of A Kids Book About, is a friend of mine. He and I have been in a conversation now together over a decade really about what we're experiencing and are going to continue to experience in our country and in our culture as white people continue to resist their own exploration on the topic of their ethnicity. What does it mean to be white? While we've been talking about it for quite some time, I think in this particular moment in 2020 and as we look ahead, Jelani feels that this is an incredible pivot that's taking place. Now's the time to make sure that we're having this conversation. He asked, and I said yes.

Zibby: Amazing. Have you guys met before?

Jordan: We haven't.

Zibby: No? Oh, my gosh. Ben, this is Jordan. Jordan, this is Ben.

Jordan: Thank you, Zibby, for bringing us together.

Zibby: [laughs] No problem. I'm surprised that Jelani hasn’t organized some sort of meetup with everybody.

Jordan: It's been crazy. It's been very busy over the last few months. With the pandemic, obviously, we haven't had a chance to do an in-person mixer or anything like that, but hopefully soon.

Zibby: I get it. When you were both writing your books, what were some of the things that you wanted to make sure to include? How did you figure out how to get them into bite-size information for kids? Obviously, writing for adults is way different. What's your experience been like talking to kids? I know, Jordan, you did a whole deep dive on fatherhood, so I know you're familiar with that. Ben, you're part of this contingent, so you're actively organizing people, but what about kids?

Jordan: For me at least, it was really, really challenging and really uncomfortable, somewhat, of a process because this is such a deep issue. There's also just a lot of nuances. Writing a children's book forces you to make a lot of generalizations. That's the one part that I really struggled with, was making the generalizations. Of course, there's exceptions of all of these things. I have to have confidence in the parent or the adult that will be reading with these children and helping contextualize what's in the book and offer some of that nuance themselves based on their own lives and their own family experiences. I just have to trust that process. I haven't gotten too much critique or pushback yet, but I'm steady waiting for it. That was definitely the hard part, was making those generalizations and knowing obviously there's exceptions to all these things. The Kids Book About team, they have this process down pat. They really supported me in being comfortable with that and trying to tell the story and also not shy away from some of the harsh realities. I wasn't sure how to phrase some of those things about genocide, about slavery. I was very grateful that they were not shying away from those things.

Zibby: It is hard to package up genocide in a very -- when other books are about sleeping sheep. Those are the choices at the end of the day. How about you, Ben?

Ben: I have three children, two biological white girls and my son is half Vietnamese, half Mexican. We've been having a conversation about their whiteness for as long as they really can remember. That really was, for me, where this started to percolate as someone that lives in a very multicultural community. The work that I do intentionally engages communities of color. Part of what I was longing for was a method to try to translate our internal family conversation to a conversation that could spread with the world. I live in Portland, Oregon. When George Floyd was murdered and the protests began, of which those protests continue, I think the white kids in my city were seeing these protests and were asking questions about they meant for them. It struck me that there are not a ton of resources out there to talk to white kids about their white privilege in a manner that actually asks them to acknowledge it, to give it up, and to use it for the benefit of others. So much of the narrative around white privilege has been co-opted by a cultural war that's questioning whether or not white privilege even exists. When you ask the question, what does it mean to be white in a moment when we're asking big questions about race? it felt like now was the time to do that. For me, it was a bit of a translation of taking evening pajama conversations and putting them in a book that could be brought to homes across the country.

Zibby: You did it.

Ben: I hope so.

Zibby: Congratulations. Even the format, I feel like this is totally digestible for kids. I have a six and seven-year-old and then two thirteen-year-olds. Although, forget about getting them to do anything. The little guys, I can still read to. The colors, the message, the questioning, it's an engaging versus didactic type of read for kids, which I think is so important. What is really exciting you guys? Is it that this content is getting out there? Is it that you're a part of it? There must be something that made you stop and feel passionate enough about this that you were like, yes, I'm dedicating all this time to writing it and marketing it and getting it out there. What is it for you personally that made you the ones to do this?

Jordan: For me personally, I'm just really excited to be in company with folks like Ben and the other authors. We're all really focused on this really positive message for our young people about love and hope and resistance and change and acceptance. At the end of the day, that's probably what the Kids Book About legacy is going to stand for because all the books to date have been in that vein. I think it's going to have a really positive impact over the long term. I'm also just really excited to be equipping parents and teachers with something to help get these conversations started with their kids and their students.

Ben: Zibby, what's exciting to me about the book and a kids' book about any of these topics that are being discussed, but particularly the topics around race, is it feels that we are pushing conversations with a generation of kids that are going to be in leadership in a really critical moment in our country's history. I imagine that we're looking at a twenty-year arc in this conversation. Some of the elders, some of those generations that have gone before us, are not prepared to have this conversation at scale. We're seeing a polarization as a result of that. There are many leaders that have huge concerns about our inability to have a conversation about race and the wealth gap in our country. As a result of that, the inability to have that conversation, what it's led to is those that are in previous generations rejecting the idea of critical race theory or systemic racism altogether. To be able to make a deposit into a generation of young, white kids to ask these questions in critical moments of their formation, for me, feels like it's a very strategic move for a twenty-year conversation that has to take place with a quickening pace for the days ahead.

Zibby: In twenty, thirty years, we'll be watching the election. They’ll say, it all started when I read this children's book.

Ben: Yeah, that's right. I'm sure that's what it will be.

Zibby: It's going to be that. I had it on my shelf. I kept looking at it. There you go. You never know. I think about different children's books all the time. It's a good time to really get in there. If you can learn a whole new language without even trying that hard, it's a good time to learn a lot of concepts that when you're older, maybe they're too challenging, or not too. I'm not saying anyone should give up. I'm just saying the impressionable brain at the young age is a good time to get positive messages around. Do you think that getting to a place where kids don't see race is where you want things to go? Would your goal be having kids today grow up acknowledging -- when I was growing up, I feel like everybody was like, we don't see race. In all my education and all that, I didn't even realize it was a thing until I was older and people were polarized around it. I grew up in a really diverse education environment and all this stuff. I didn't think twice about it. There's so much focus now on race that I feel like, especially for little kids, they might not have even really noticed it before. Is it better to notice and probe the differences, or it is better to just be like, her skin's a little darker than mine, but I don't know, whatever? Do you understand my question? [laughs]

Ben: Yeah. I'll take a crack at that. Jordan's book really addresses this even uniquely beyond mine. I think it's absolutely essential that we have conversations about the black experience in America and the experience of what it means to be a part of the Latinx community. What we have not done historically is taught white kids about their whiteness and helped them to understand that their whiteness has been rooted in a systemic unearned advantage that they benefit from and have been benefitting from for some time. When we think about race and whiteness in particular, which is what this book is certainly focused on, we won't be able to have a conversation about race that builds bridges until white people learn about their whiteness. I do this a lot. When I talk to white people, I ask them, when was the last time you ever thought about what it means to be white? The vast majority of white people can't answer that question. They're not thinking about their whiteness. They don't understand where the terms came from. They don't understand how deeply rooted the systemic unearned advantage has been. They certainly are uncomfortable with exploring the topics in Jordan's book around slavery and genocide and the laws that were created. From my perspective, we won't be able to move forward until white people understand their whiteness and then begin to wrestle with it in a way that's critical. That means that to understand your whiteness, you have to understand how whiteness has created an adverse effect at a systemic level for people of color in our country. That needs to be named and parsed out carefully in my view. Jordan, what do you think?

Jordan: I agree with everything you said there, Ben. Thank you. For me, this is not about trying to work towards a colorblind society. It's about trying to work towards an inclusive, vibrant society where these inequities and injustices don't exist. The book, for me, is helping encourage young people to take into consideration the history behind the inequities that we see today. That goes not just for race, but I want them to understand that too for gender, for sexuality so we can contextualize these inequities and then work our way backwards to try and address those root causes. If the book helps train that mental framework for young people, then I'll be very, very pleased.

Zibby: As authors in addition to, I would say, advocates and almost history teachers and documentarians and all the other amazing things you guys do, as authors when you sat down to write this book, what did you learn about yourselves in terms of any sort of advice on writing children's books, on getting your messages out? What would you tell someone else who was like, you know what, I want to, A, help this problem, and B, do so through reaching kids? What would you tell them? How can they do a good job?

Ben: I would say the key here is let your life speak. Look back on your life and try to identify that thread that brings you to this point where you have a longing to write, you have a longing to communicate. So much of an author's experience is really about exploring their own identity. For me as a white person and my own white experience being able to write about whiteness and then to want to talk to other white people about this is really a culmination of a journey that I've been on that pivots me to this moment to enter into a new chapter of that journey. It was just as important for me to come to the text looking for my own growth in light of my own journey. Any aspiring authors or anyone that wants to communicate to kids I think needs to also imagine how that topic impacts them and to write from that intimate personal space.

Zibby: I'm feeling like, is there a memoir coming on the heels of this, Ben?

Ben: A Kids Book About...

Zibby: A Kids Book About Ben's Life. Is that in the works as well? [laughs]

Jordan: I agree with everything Ben said there. Picking up on those notes as well, I think people should value their own lived experience. A lot of people just don't. They don't think of their own experiences. Their own stories have value for other people to know and learn from. That's one of the biggest things I'm always pushing for as someone who does documentary work. Share this story because someone is going to benefit from it. That's one thing. Like Ben said, write from that place. Explore your own identity, your own experiences. The other is a more practical, tangible thing. There's a lot of fantastic children's books out there that deal with issues of race, gender, sexuality, culture, but they don't get out there because the children's publishing industry is so rigid. There's just only a few big players. There's a lot of these really fantastic books that just don't have this type of reach. What I'm learning from A Kids Book About, because they’ve created a really valuable pipeline for new kind of content to go directly to consumers instead of having to go through the big players in the children's book publishing industry, the marketing that they're doing is just incredible. With some of our books being included on Oprah's wish list, the kind of reach that that's getting is just -- I never would've imagined for this children's book. Trying to pull from some of the lessons from what A Kids Book About is doing in terms of the marketing and the outreach and not having to go through the big players in the industry, I think people can learn from as well.

Ben: Well said.

Zibby: Yes, great point. Definitely, the advice is get on Oprah's list. I'm going to put that at the top of my list.

Jordan: Easier said than done.

Zibby: That helps. That definitely helps. First, you have to have great content. That's the first stop. Thank you both. I'm glad I could be here to introduce you to each other. Maybe now you guys can go have a nice, interesting, dynamic, thoughtful conversation of your own without me bothering you with my questions. Thank you for contributing to society and trying to help the next generation. That's really admirable of you. Big thumps up as a parent and whatever I am these days, as a person. [laughs] Thanks. It's awesome.

Ben: Thanks for having us on your show.

Jordan: Thank you so much, Zibby.

Zibby: Buh-bye.

Jordan: Take care.

Liz Tichenor, THE NIGHT LAKE

Zibby Owens: Welcome, Liz. Thank you so much for coming on "Moms Don't Have Time to Read Books" to discuss The Night Lake.

Liz Tichenor: Thank you for having me.

Zibby: Your subtitle is A Young Priest Maps the Topography of Grief. When I saw this whole cover and subtitle and everything, I was like, oh, my gosh, I have to read that. That must be really amazing. It was. Can you please tell listeners basically what it's about, the period of time, and what happened? What made you turn your experience into a book?

Liz: I had been moving towards being ordained as a priest for a long time. When it actually came to pass, when it happened, my life was a really different landscape than what I had imagined it would look like at that point. My mom had been sick for a long time. She struggled with alcoholism for many, many years. It was just a couple of months before I was ordained as a priest that she died. She died by suicide. It was just awful and unexpected that it would end that way. Then a few months later, I was ordained. It was an unusual setup in some ways. I had decided to take an extra year in graduate school. I was ordained and then was continuing the academic year studying more. I began my first call splitting my time between a parish and a summer camp and conference center. My second child, a son, was born about maybe three months after I began at that parish. I started and was just getting my feet under me in this new job and not just a new place, but my role in doing that work. You learn everything in school, but it's pretty different when you're actually out trying to do the work and discover how you're going to do that work. I went onto maternity leave.

Then forty days later, our son, Fritz, died suddenly, totally unexpectedly. He'd been this huge healthy -- everybody said, he's so big. Then all of a sudden, I was the parent of a dead baby. There are statistics, but I was young. I was healthy. I don't think I had ever really considered that that would be the shape of my life, and maybe especially because my mom had just died. One of the things that people said to me, wait, but you just went through that. How can you be going through this now? It was not even a year and a half later. When I went back to work, it was maybe a month later after he had died. I was still learning how to do this job. There are a lot of different ways to inhabit it. It hasn’t been that long, really, that women have been ordained. It's still a job, a role, that is so influenced by the many centuries of male-dominated leadership. What I came to see pretty quickly was that I actually couldn't separate my grief and what I was doing there with authentically showing up. Yet my job was to lead people towards hope and to look for how the moral arc of the universe is bending towards justice and where we might find good news together. In some ways, that felt so at odds with the really dark and desperate place where I so often found myself in those days.

As I began sticking my toes in the water a little bit, I discovered the more that I showed up authentically, the more I was honest about where I was wrestling, the more it seemed to work, what I was trying to do in my job. The book is a sort of winding road through that process of grieving these two beloved people, of trying to discover how to survive that. There were times when I wasn't sure I was going to come through on the other end or what that would look like. Then trying to both lead a community and also parent -- my daughter was two and change when our son, Fritz, died. Wrestling, do we do this again? We wanted to raise siblings. How? How do we do that? It's a story of, what is too much? and how we try to rise to that and live through it anyway. To the second part of your question, why I decided to write the book -- I looked it up the other day. I was curious. Brené Brown's book, Daring Greatly, was published about two weeks after my mom died. There was this surge as that got traction. I found that book. A lot of people found that book. There started to be more conversation about this intersection between leading and being vulnerable. It's not something that I saw a whole lot of. I was not taught to preach vulnerably. We're taught to be really careful not to use the congregation as your therapist, and I totally support that. The other adage that I heard which I, to a certain extent, agree with is to preach from your scars not from your wounds. Don't go up there and bleed all over everybody. That makes a lot of sense to me.

It breaks down when you're in the midst of life. Life is happening. All these people knew that my mom had just died by suicide. They knew that I had just lost our baby totally unexpectedly. For me to get up there and unpack our sacred texts or try to point to different ideas leading us forward and not bring myself into it, it felt dishonest. Somehow, to the concern of some more traditional folks, I started doing that. I started being just real and sometimes raw in what I shared. It wasn't for everybody. Not everybody is ready for that. The folks who needed it, the response was really stunning. I remember one day several years ago, someone who's now a friend came to me after hearing one of these and said, "Okay, so when are you going to write that book?" She had been through some really tough stuff too, just a terrifying diagnosis and life unraveling and then coming back together on the other side of that. I couldn't really get away from it. It felt like it needed to come out of me.

Zibby: Wow. This is such a powerful story. How did you maintain your faith in God after everything that happened to you?